Last time in this article series, I determined what a Commander deck is: namely, it’s some collection of Magic cards helmed by a commander. I also defined a commander as exactly one or two Magic cards. That begs the question: what, exactly, is a Magic card?

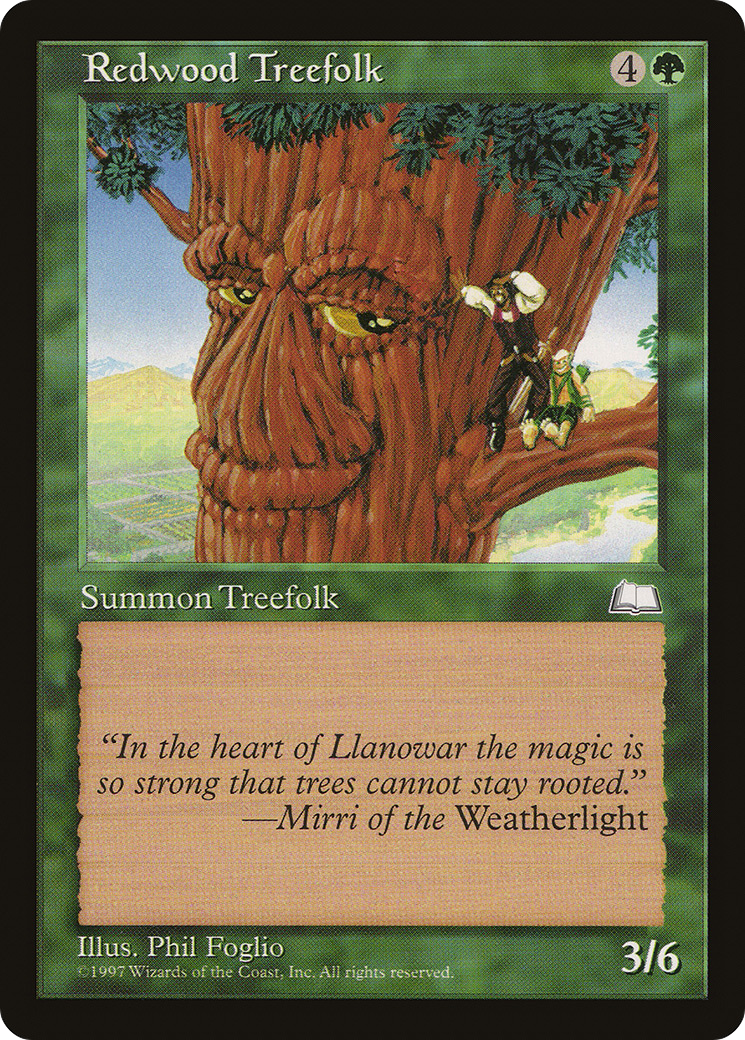

Well, that’s a Magic card, obviously. Most cards have a name, a type, a cost, and text printed in its text box. Some cards have printed power and toughness; others have fancy loyalty abilities; others still have multiple faces. As the game evolves, so does the complexity of its pieces, and with thirty years of card stock to go through, it’s an astronomical amount of data to find and catalog.

So in order to build a recommendation system, I’d first have to build a database of every card in Magic. It’s a required step. If the system doesn’t know what cards exist, then it obviously can’t recommend them. Needless to say, that’s a project in itself, and one that would require several full-time engineers to maintain and update. I can’t do that on my own, so that’s it — project over, right? Wrong.

Enter Scryfall

The good news is that I don’t have to build a comprehensive database of Magic cards, because someone else already did. Scryfall is not just a powerful Magic: the Gathering card search engine. It also hosts a comprehensive Magic API.

API stands for application programming interface. An API is a specification describing how programs interact; it lists the operations you can call. If you’re not a software engineer, you can think of it like a restaurant’s menu. The restaurant publishes the list of food it sells (the API), and when you’ve made your decision, you can place your order (or call the API).

In practice, the acronym API refers not only to the specification, but also to an implementation of the specification. In my metaphor, it would be like referring to both the menu and the restaurant simultaneously. I know that’s confusing, but it’s the same principle as saying you’re ordering Chipotle on DoorDash. Strictly speaking, you’re ordering burritos from Chipotle, but that distinction doesn’t really matter; it’s just how us computer programmers speak sometimes.

As an API, Scryfall is useful for my project in a ton of ways. It has a well-defined Card object that includes anything you could possibly care to know about a given Magic card. As an example, here’s the Scryfall API representation for Redwood Treefolk. You can see everything: its artist, the set it was printed, what formats it’s legal in, the works — and since Scryfall has already collected this data for every single card in the game, that’s a massive amount of work I don’t have to do myself.

Of course, information is useless unless it’s accessible, and thankfully, Scryfall also publishes bulk data downloads of everything they’ve cataloged. If I want the most up-to-date records, all I have to do is keep pulling the latest bulk data files and ingesting any new cards into my database. They even go above and beyond by publishing information about any changes they’ve made in their migrations file, so if a card was erroneously uploaded and later deleted, I can know about it.

The best part of all of this is that Scryfall is so unbelievably useful that practically every Magic website relies on it in some way, shape, or form. That means that deck building websites often represent cards internally using Scryfall’s IDs instead of coming up with new ones themselves, so all I have to do to store accurate card counts is to keep a list of Scryfall IDs. It seems like a minor point, but if this wasn’t the case, I would have to count cards based on their names — and not only is Magic published in multiple languages, but some cards that are the identical in terms of gameplay actually have different names across printings, like Trailblazer’s Boots and Lórien Brooch.

What About My Needs?

Now, the answer to “what’s a card” is pretty definitively “Scryfall’s Card Object,” but it’s actually overkill for my purposes. Recommendation systems only care about cards as game objects, and, drilling further down, they only actually care about the relationships between said game objects. EDHREC doesn’t need to know that Shock deals two damage to any target; it only needs to know that a lot of Ojer Axonil decks run it.

It’s been three long articles, but it’s actually, finally time to do a thing. Here’s the card object I created for my recommendation system:

public record OracleCard

{

/// <summary>

/// The name of the card.

/// </summary>

public required string Name { get; set; }

/// <summary>

/// The Scryfall Oracle ID.

/// </summary>

public required string OracleId { get; set; }

/// <summary>

/// The representative Scryfall ID, used for display.

/// </summary>

public required string RepresentativeScryfallId { get; set; }

/// <summary>

/// The color identity of the card.

/// </summary>

public required ColorIdentity ColorIdentity { get; set; }

/// <summary>

/// The types of the card.

/// </summary>

public required CardType CardTypes { get; set; }

/// <summary>

/// The mana cost of the card.

/// </summary>

public required string ManaCost { get; set; }

/// <summary>

/// The raw type line of the card.

/// </summary>

public required string TypeLine { get; set; }

/// <summary>

/// The Oracle text of the card.

/// </summary>

public required string OracleText { get; set; }

}It includes the bare minimum I need for the functionality I want to recreate. It stores the card’s name, mana cost, and type line as a string, or a blob of text.

Also included as a string is the card’s Oracle text. The Oracle text refers to the instructions printed on the card; it’s named Oracle because that’s the old name of Wizards of the Coast’s Magic card database, which is the source of truth for card rules.

Some cards are worded differently today compared to when they were originally printed twenty years ago. An old copy of Oubliette has different printed text than a modern copy of Oubliette, but in-game they play exactly the same way — by following the gameplay instructions defined by their Oracle text.

That leads to the next field I want to highlight, the Oracle ID. While Oubliette, the card, has multiple print runs, my recommendation algorithm only cares about Oubliette, the abstract game piece. Scryfall assigns each physical printing a unique identifier, called the Scryfall ID — but it also assigns each game object a unique Oracle ID. As an example, the two different printings of Oubliette above have different Scryfall IDs, but they still share the same Oracle ID: c753e9e3-9374-4e3c-8622-94576a8c1da3.

This is important for me to know because I’m ingesting training data from deck building websites, which actually do care about different printings. A player who’s recording the contents of a deck they physically own may want to note which version of the card they’re in possession of, since, as an example, the price of cards can vary wildly among different printings. Ravnica Remastered’s Birds of Paradise costs $9.10 at time of writing, while a Seventh Edition foil Birds costs $1423.00.

Still, I will need to display a picture of something that exists in the real world when a card gets recommended, and for that we need to nominate a single printing as a candidate. That’s the purpose of the RepresentativeScryfallId field, and it’s populated based on the Default Cards bulk data download, which includes the latest English printing of each game object. I’ll eventually have to build a mapping of all Scryfall IDs to their corresponding Oracle IDs, but that’s for a later article.

Finally, we have the ColorIdentity and CardTypes fields. The ColorIdentity field stores the card’s color identity, which I’ll need to cull illegal recommendations from my website. The CardTypes field stores the card’s types, which I’ll use to categorize the recommendations when displaying them. You’ll notice that they’re not strings like everything else, though; they’re stored as their own unique types. Here’s what those look like:

[Flags]

public enum ColorIdentity

{

None = 0,

White = 1 << 0,

Blue = 1 << 1,

Black = 1 << 2,

Red = 1 << 3,

Green = 1 << 4

}

[Flags]

public enum CardType

{

None = 0,

Artifact = 1 << 0,

Battle = 1 << 1,

Conspiracy = 1 << 2,

Creature = 1 << 3,

Dungeon = 1 << 4,

Enchantment = 1 << 5,

Instant = 1 << 6,

Kindred = 1 << 7,

Land = 1 << 8,

Phenomenon = 1 << 9,

Plane = 1 << 10,

Planeswalker = 1 << 11,

Scheme = 1 << 12,

Sorcery = 1 << 13,

Vanguard = 1 << 14

}This is called an enumeration, or enum. They’re a way to programmatically represent choices. For example, an enum for the cardinal directions might include the values North, South, East, and West. Each choice in an enum is associated with a number, which is useful for storage and retrieval. You could have North equal , South equal , and so on.

For the ColorIdentity enum, I’ve set a colorless identity equal to , a white identity equal to , a blue identity equal to …okay, I should probably explain that.

There are five colors in Magic: white, blue, black, red, and green. Despite that, there are actually thirty-two color identities, since each color identity is a combination of some, none, or all of the five colors. White-blue is a color identity; so is blue-red-green; and so is no colors at all. If my deck is Azorius (white-blue), then the set of legal cards I can recommend includes all Azorius cards, all white cards, all blue cards, and all colorless cards.

If I were to type out all thirty-two color identities in no particular order, calculating which cards are legal to include in each deck would be a nightmare. So, I’m using a trick that’s based on how computers represent numbers. Time for a little math lesson.

Ones and Zeroes

It’s common knowledge that computers represent numbers in binary — ones and zeroes, such as . Less common is how to actually read that representation as a number you’re used to.

Let’s start by looking at an ordinary number: . Nice! In the ones place, you have the number , and in the tens place, you have the number . The in the tens place actually means you count that digit as six tens; in other words, . This system is called decimal because each place has ten possible digits: zero through nine.

Now, here’s the important part. The fact that there’s ten digits means that each place actually represents how many tens there are raised to that place’s power, starting from zero. The in the tens place means . The in the ones place means — and since anything raised to the power of zero equals one, you ultimately just end up adding .

The difference in binary is that instead of there being ten possible digits for each place, there’s only two. Let’s look at . We have in the first place, in the third place, and in the seventh place. So, adding that up, we have . Nice!1

Back to Magic

So what does this have to do with the weird ColorIdentity representation? Let’s take a look at that again.

[Flags]

public enum ColorIdentity

{

None = 0,

White = 1 << 0,

Blue = 1 << 1,

Black = 1 << 2,

Red = 1 << 3,

Green = 1 << 4

}Let’s talk about that funky operator, . That’s the bit shift left operator; it means “take the number on the left, and shift the numbers in its binary representation to the left by this many places.”

As an example, the result of would be this: take its binary representation, , and move the numbers in over to the left by one to make . In other words, .2 So, the actual numbers here in decimal are as follows:

[Flags]

public enum ColorIdentity

{

None = 0,

White = 1,

Blue = 2,

Black = 4,

Red = 8,

Green = 16

}This still looks like a big waste of time compared to just setting them to zero through six like a normal person. But, maybe you’ll see the value once we represent it in binary:

[Flags]

public enum ColorIdentity

{

None = 0b00000,

White = 0b00001,

Blue = 0b00010,

Black = 0b00100,

Red = 0b01000,

Green = 0b10000

}Notice something? Every single color defined here has exactly one bit set, and thus, we could represent each unique color identity as combinations of these set bits. Want the Azorius color identity? Simply add white and blue: . Now all I have to do to determine if a color identity includes a color is to check if the specific bit associated with that color is set to .

Each bit is a flag indicating whether a color is present; that’s what [Flags] means. This approach makes it possible to store the colors in the color identity (as well as all the card types of the card) in individual, single numbers instead of big lists of checkboxes.

public static string ToColorString(this ColorIdentity colorIdentity)

{

var colorString = string.Empty;

if (colorIdentity.HasFlag(ColorIdentity.White))

colorString += "W";

if (colorIdentity.HasFlag(ColorIdentity.Blue))

colorString += "U";

if (colorIdentity.HasFlag(ColorIdentity.Black))

colorString += "B";

if (colorIdentity.HasFlag(ColorIdentity.Red))

colorString += "R";

if (colorIdentity.HasFlag(ColorIdentity.Green))

colorString += "G";

return colorString;

}To show how useful this is, here’s a function that takes a ColorIdentity and outputs a string for that color identity, like WUBRG. It checks each flag individually to see if it’s set, and if it is, it adds that specific character to the output string.

I can also easily check if a card is a legal include in a deck using one last trick. Suppose you have the color identity for white, , and the color identity for Bant (white-blue-green), . To check if you can legally include a white card in a Bant deck, you’d use the bitwise and operator, (represented in code as &).

The bitwise and operator works like this: take the binary representation of the number on the left, and set every in it to unless the binary representation of the number on the right also has a in that place.

Coming back to our example, has only its lowest bit set, and also has that bit set, so ; it’s unchanged.

Conversely, let’s try something that’s not a legal include: a Rakdos (red-black) card in a Gruul (red-green) deck. That’s . Since there’s a bit set in the left number that’s not set in the right number, , which is a different number from what we’re checking.

A card with color identity represented by is a legal include in a deck with a color identity represented by if and only if . This is a stupid fast operation on computers, and it makes checking legality a breeze.

Next Time

So, we’ve got a representation of each card down pat — but we still have to download those cards from Scryfall and store them somewhere for our own use. That’s for another time, though. I hope the math hasn’t scared you off, and if it hasn’t, see you then!

Footnotes

-

You can apply this to other bases, too. Hexadecimal is something you might have seen on that blue screen when your computer crashes; it looks like . In hexadecimal, there are sixteen possible digits in each place; through , and then the letters (for ten) through (for fifteen). Here we have . Blaze it! ↩

-

The bit shift left operator is basically the same thing as multiplying by a power of two; . ↩